I received a free copy of this book in exchange for a fair and honest review. All opinions are my own.

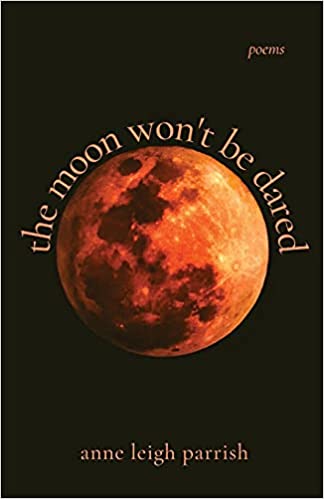

Author and Poet Anne Leigh Parrish explores nature, love, and the uphill battle many women face in a male-dominated society in her book, “The Moon Won’t Be Dared”.

The Synopsis

The poems in the moon won’t be dared by award-winning author anne leigh parrish ponder nature, love, ageing, and the impossible plight of women in a male-dominated society. Love and reverence for beauty blend with harsher truths of betrayal and brutality. Throughout, there is an overriding sense that life is full of magic, and that to wonder is a lovely gift.

The Review

Such an incredibly beautiful and emotionally-driven collection of poetry! The author has expertly crafted a collection that touches the soul and navigates the human experience with vivid imagery and succinct writing. What struck me immediately was the author’s use of no capitalization in her writing, allowing the words to flow smoothly and with tremendous insight into the struggles of everyday life and the world as a whole.

The balance the author found between narrative-style poetry and more personal and relatable storytelling with a healthy dose of heartfelt themes that inspire us all to stop and really examine the world around us. From the fires raging on the US West Coast and the rise of global warming to abuse and the loss of a loved one, the author conveys each topic and poem with such conviction and depth, and when accompanied by the engaging artwork makes for a memorable reading experience.

The Verdict

A remarkable, emotional, and thoughtful collection of poetry, author Anne Leigh Parrish’s “The Moon Won’t Be Dared” is a must-read poetry collection of 2021! With a mesmerizing blend of awe-inspiring imagery and thought-provoking words that stirred up the emotions within us all, readers will be hard-pressed to keep away from this fantastic collection. If you haven’t yet, be sure to grab your copy today!

Rating: 10/10

About the Author/Poet

Anne’s first fiction publication appeared in the Autumn 1995 issue of The Virginia Quarterly Review. That story, “A Painful Shade of Blue,” served as the basis for more fiction describing the divorce of her parents when she was still quite young. Her later stories focused on women struggling to find identity and voice in a world that was often hostile to the female experience.

In 2002, Anne won first place in a small contest sponsored by Clark County Community College in Vancouver, Washington. In 2003 she won the Willamette Award from Clackamas Community College in Oregon; in 2007 she took first place in highly esteemed American Short Fiction annual prize; and in 2008 she again won first place in the annual contest held by the literary review, The Pinch.

The story appearing in American Short Fiction, “All The Roads that Lead From Home” became the title story in her debut collection, published in 2011 by Press 53. The book won a coveted Silver Medal in the 2012 Independent Publisher Book Awards. Two years later, a collection of linked stories about the Dugan family in Upstate New York, Our Love Could Light The World, was published by She Writes Press.

Her debut novel, What Is Found, What Is Lost appeared in 2014. This multi-generational tale speculates on the nature of religious faith and family ties, and was inspired by her own grandparents who emigrated to the United States in 1920.

A third collection of short stories appeared in 2017 from Unsolicited Press. By The Wayside uses magical realism and ordinary home life to portray women in absurd, difficult situations.

Women Within, her second novel, was published in September 2017 by Black Rose Writing. Another multi-generational story, it weaves together three lives at the Lindell Retirement home, using themes of care-giving, women’s rights, and female identity.

Her third novel, The Amendment, was released in June 2018 by Unsolicited Press. Lavinia Dugan Starkhurst, who first appeared in Our Love Could Light The World, is suddenly widowed and takes herself on a cross-country road trip in search of something to give her new life meaning.

Maggie’s Ruse, novel number four, appears October 2019 from Unsolicited Press, and continues with the Dugan family, this time focusing on identical twins, Maggie and Marta.

What Nell Dreams, came out in November 2020 from Unsolicited. This collection of sixteen short stories also features a novella, Mavis Muldoon.

The next installment in the Dugan families series, A Winter Night, was released in March 2021 from Unsolicited Press. Anne’s fifth novel focuses on eldest Dugan Angie and her frustrations as a thirty-four-year-old social worker in a retirement home.

Anne has been married for many years to her fine, wise, and witty husband John Christiansen. They have two adult children in their twenties, John Jr., and Lauren.

About Lydia Selk

Lydia Selk is an artist who resides in the pacic northwest with her sweet husband. She has been creating analog collages for several years. Lydia can often be found in her studio with scalpel in hand, cat sleeping on her lap, and a layer of paper confetti at her feet. You can see more of her work on instagram.com/lydiafairymakesart